For Leo Berwick’s analysis of the most recent Bill to implement the Clean Technology Investment Tax Credit, please click here

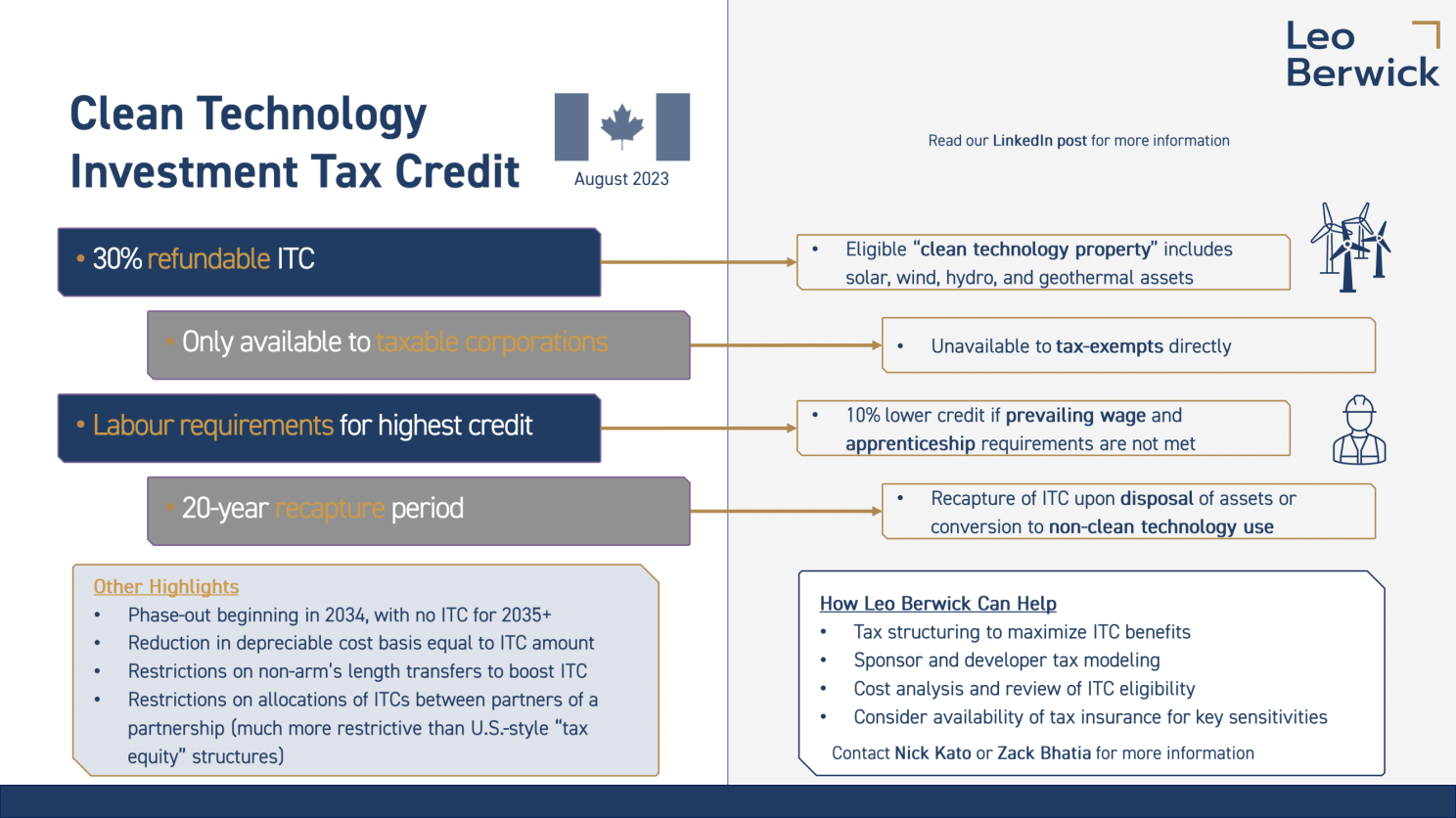

On August 4, 2023, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance Chrystia Freeland published legislative proposals (the “Proposal”) relating to various incentives discussed in Budget 2023, including the new Clean Technology Investment Tax Credit (“ITC”).

Leo Berwick has read through the Proposal and summarized the highlights below. Note that these rules are continuously developing and this post is being reviewed and updated in real-time. If you have further questions about the Proposal or the Clean Technology ITC, please contact Nick Kato, Managing Partner (nick.kato@leoberwick.com) and Zack Bhatia, CPA, Vice President (zack.bhatia@leoberwick.com).

1. ITC Calculation

Like many existing and historical ITCs in Canada, the Clean Technology ITC is computed by multiplying the applicable tax credit rate by the capital cost of eligible property. In the case of the Clean Technology ITC, the “regular” tax credit rate is 30% for eligible property acquired on or after March 28, 2023. Note that the tax credit rate is reduced to 15% for property acquired in the 2034 calendar year and is fully reduced to nil for property acquired in 2035 onwards.

The above references a “regular” tax credit rate. As discussed further below, taxpayers must elect into various labour requirements in order to qualify for the regular tax credit rates. These labour requirements were briefly mentioned in Budget 2023 and mimic the U.S. labour requirements introduced as part of the Inflation Reduction Act in 2022. Failure to elect into and qualify for these requirements results in the taxpayer only being eligible for the “reduced” tax credit rate. The reduced tax credit rate is generally 10 percentage points lower than the regular tax credit rate (i.e., 20% until 2034, and 5% in 2034).

2. Eligible Cost

The ITC benefit is a function of the capital cost of “clean technology property” acquired by the taxpayer in the year. Consistent with Budget 2023, clean technology property includes (but is not limited to):

- Wind energy conversion systems, including wind-driven turbines, control and condition equipment, support structures, powerhouse, and certain transmission equipment;

- Fixed location solar photovoltaic equipment, including solar cells or modules and related equipment including inverters, control and conditioning equipment, support structures and certain transmission equipment;

- Concentrated solar energy equipment, including electrical generating equipment, solar reflectors, thermal receivers, thermal energy storage equipment, heat transfer fluid systems, and certain transmission equipment;

- Hydro-electric installations, including electrical generating equipment, canals, dams, dykes, overflow spillways, penstocks, powerhouse, control equipment, fishways or fish bypasses, submerged cable equipment, and certain transmission equipment;

- Geothermal equipment used for the purpose of generating electrical energy, heat energy, or a combination of both, excluding equipment that also extracts heat from fossil fuels;

- Batteries and certain other fixed location energy storage property; and

- Non-road zero-emission vehicles and charging stations.

Additional requirements clarified in the Proposal include that clean technology property must be situated in Canada, must be intended for use exclusively in Canada, and must not have been used or acquired for use for any purpose before it was acquired by the taxpayer.

Key costs that are excluded from the capital cost for purposes of the ITC include:

- Capitalized interest and financing fees;

- Certain additional costs arising from non-arm’s length transfers (see further below);

- “Distribution equipment”, which generally includes transmission lines and other equipment that is used to transmit 75 percent or less of the annual electricity energy generated by the electrical generating equipment. Note that such equipment that is used to transmit more than 75 percent of the annual electricity energy generated is considered to be “transmission equipment” and is generally eligible for the ITC;

- Certain equipment that uses any fossil fuel in operation;

- Buildings or structures, except structures whose sole function is to support or house concentrated solar energy equipment.

Leo Berwick Insights: Investors will want to ensure that their claims are supported with detailed cost studies/analyses to ensure that all ITC-eligible costs are identified. Based on our experience in the U.S., we would also expect tax insurance to begin to play more of a role in renewable energy deals in Canada on a go-forward basis to protect against the risk of credit eligibility being challenged. Key areas of sensitivity are the ITC eligibility of costs incurred as well as any premiums to cost basis that are created on transfers between parties, in particular where such parties have common ownership.

3. Basis Reduction

The Proposal clarifies that the depreciable tax basis for the particular property will be reduced by the ITC claimed. E.g., for $100 of eligible costs, assuming that a 30% ITC is claimed, a taxpayer will reduce the depreciable basis in the particular property by $30 and therefore will be able to claim depreciation benefits on only $70.

4. Eligible Taxpayers

The Proposal clarifies that the Clean Technology ITC is meant to be available only for taxable corporations, which excludes the ability for tax-exempt entities (e.g., registered pension funds, Crown corporations) to claim the ITC directly. However, the Proposal does not provide any difference in treatment for taxable corporations controlled by tax-exempt entities or non-residents. More guidance on the ability for tax-exempt entities to claim the ITC through taxable corporations would be helpful.

Leo Berwick Insights: The Budget implied that the credit would be unavailable to tax-exempts, so this is no surprise. However, with the introduction of recapture rules (discussed below), it appears that tax-exempt investors in energy assets will need to consider the trade-off between (i) investing through taxable corporations to provide access to the ITC, versus (ii) investing in flow-through form to take advantage of tax-exempt status. This is a modeling exercise that Leo Berwick can assist with.

Furthermore, we note that the Budget mentioned a 15% Clean Electricity ITC that would operate in similar capacity to the Clean Technology ITC but would be available to non-taxable corporations. The Proposal does not provide any information regarding the Clean Electricity ITC or its interaction with the Clean Technology ITC. Further guidance would be helpful to confirm whether any other alternatives are available to tax-exempt entities/pension funds, especially given the amount of capital they deploy in the Canadian market currently.

5. Refundability

As mentioned, the ITC is proposed to be refundable. This means that the ITC will not only offset the taxes otherwise owed by the taxpayer but will also generate a tax refund to the extent that the ITC exceeds the taxes otherwise owing.

Leo Berwick Insights: The refundability of the ITC creates a meaningful timing difference compared to the U.S. ITC counterparts, which are non-refundable (only offset taxes). Developers of eligible assets in Canada will want to compare (i) the benefit of operating the assets (or retaining a partial interest in the project) in order to gain access to the benefits of the ITC to (ii) the benefit of selling developed projects at a premium with the buyer’s ITC benefit priced in. This is a modeling exercise that Leo Berwick can assist with.

6. Timing of ITC

The Proposal clarifies that, while eligible costs may be incurred throughout the construction period, the ITC is only available to be claimed once the property is available for use. Typically, we would expect this date to be as of the commercial operation date (COD) when it has been demonstrated that the property is capable to be used for its intended purpose.

Leo Berwick Insights: Note that a requirement for the ITC is that the acquired property has not been used for any purpose before being acquired by the taxpayer. As such, care should be taken by investors to acquire externally developed assets at the right time in order to gain access to the ITC, i.e., before substantial completion and the commercial operation date.

7. Recapture

A new feature of the Proposal is the ITC recapture rules. These rules appear to operate similarly to existing ITCs and in some ways mimic the rules in the U.S. Generally, if the ITC is claimed on property and such property undergoes a recapture event within the recapture period, some or all of the ITC originally claimed will be deemed to be owed and must be repaid back to the CRA.

The recapture period in the Proposal is 20 calendar years following the acquisition of the ITC property. The Proposal includes the following recapture events:

- The property is exported from Canada;

- The property is disposed of (some exceptions for certain transfers between related parties); or

- The property converts to a non-clean technology use, which includes events that would cause the property to no longer meet ITC eligibility criteria (e.g., it is disassembled or no longer used to generate solar, wind, or water energy, it begins to be used to produce or co-produce fossil fuel energy, etc.).

The recapture amount is determined formulaically by multiplying the original ITC claimed by the ratio of the proceeds or fair market value of the asset at the recapture date over the original capital cost. For example, if the property was disposed of within the recapture period at an amount equal to 80% of its original capital cost, then 80% of the original ITC will be recaptured (regardless of when the asset is disposed of within the 20-year recapture period – e.g., year 19 vs. year 3 would provide for the same recapture). Similarly, if there was a change in use of the asset, the fair market value of the asset at the time would be compared to the original cost to assess the recapture.

The recaptured ITC is treated as tax payable.

Leo Berwick Insights: While not specifically addressed, the language in the Proposal appears to consider a disposal recapture event only when the taxpayer disposes of the applicable property. However, it would appear that, where a taxable corporation is the owner of the applicable property and is the ITC claimant, the sale of the shares of the taxable corporation should not trigger a recapture event since the taxpayer (the corporation) has not disposed of the asset. If this is the case, reasonable exit alternatives for these assets may be limited to a sale of corporate stock in order to avoid ITC recapture. This should be confirmed.

Furthermore, the Proposal does not contemplate whether a recapture event is triggered upon the sale by a partner of their partnership interest where the partnership is the owner of the applicable property. However, as discussed below, the partner (not the partnership) is generally the ITC claimant, and therefore we would expect a sale of a partnership interest to trigger an ITC recapture for that partner (but likely not for other partners).

8. Interaction with Partnerships

The Proposal clarifies the ITC mechanics for assets acquired by partnerships. Building off of existing legislation, the Proposal clarifies that the benefits will be calculated at the partnership level and allocated to the eligible partners (taxable Canadian corporations) in an amount that can be reasonably considered that partner’s share of the ITC. The ITC is claimed at the partner level. Similarly, recapture events can also be triggered based on activities by the partnership (e.g., a disposal of the assets), however the consequences of the recapture (i.e., repaying ITCs) will occur at the partner level.

The Proposal amends existing limitations regarding ITC allocations to partners to include the new ITC, namely that limited partners may only claim the ITC to the extent of their “at-risk” amount (which is generally the extent of their investment, less distributions, plus and minus income allocations). Additionally, general anti-abuse provisions regarding disproportionate allocations of ITCs between partners apply.

Leo Berwick Insights: While general anti-abuse provisions apply, the ITCs can be allocated between the partners in a manner that reasonably can be considered to reflect those partners’ share of the ITC. Factors such as the capital invested or other work performed could impact the reasonable allocations. This could present the opportunity for some flexibility in allocating the ITC between a developer and a purely economic investor, for example. While the Canadian rules seem too restrictive for U.S. “tax equity” style investment structures, there could still be opportunity for third party investors to contribute capital to energy projects in exchange for access to a large portion of the upfront tax benefits (ITC and tax depreciation benefits). This is something that Leo Berwick will be exploring over the coming months.

The Proposal restricts a limited partner’s ability to claim the ITC to the extent of their “at-risk” amount. This could impact the optimal capitalization structure for limited partnerships investing in ITC property as different financing structures could have different impacts to the at-risk amounts. Leo Berwick will be considering this over the coming months.

9. Labour Requirements

Similar to the recent U.S. rules released as part of the Inflation Reduction Act in 2022, the Proposal includes several labour requirements that a taxpayer must satisfy in order to gain access to the “regular” tax credit rate of 30%. The labour requirements are elective. Failure to elect into or meet these requirements results in the taxpayer only being eligible for the “reduced” rate of 20%.

The labour requirements contain two components:

Prevailing Wage Requirements

- “Covered workers” (i.e., workers engaged in preparation/installation of the energy property; typically manual labour) must either be paid in accordance with an “eligible collective agreement”, or in an amount at least equal to the amount of wages and benefits specified in the eligible agreement that most closely aligns to the worker’s experience level, tasks and location. An eligible collective agreement is typically a multi-employer bargaining agreement that reflects the industry standard for a given trade.

- Reasonable steps must also be taken to ensure that covered workers of other employers (i.e., contractors) working on the designated work site are also fairly compensated.

- The ITC claimant must inform covered workers at the designated work site that the work site is subject to prevailing wage requirements.

- There is some relief provided in the event the CRA determines that prevailing wages are not paid. In such instances, the ITC claimant may pay a “top-up” amount to the covered workers in order to satisfy the prevailing wage requirements.

Apprenticeship Requirements

- ITC claimants must ensure that apprentices registered in a Red Seal trade work at least 10% of the total hours worked by Red Seal workers at the designated work site.

- There is some relief provided where the ITC claimant cannot meet this requirement, for example due to labour laws restricting the amount of apprentices that may be used. In such instances, the claimant must make reasonable efforts to ensure the highest possible amount of labour hours are performed by apprentices registered in a Red Seal trade.

Leo Berwick Insights: These rules generally mimic the U.S. rules published in 2022. In our experience in the U.S. since the Inflation Reduction Act, the U.S. ITC labour requirements are insurable in some circumstances. Tax insurance could therefore have a role here with respect to insuring the risk of labour requirements not being met for the 30% Clean Technology ITC in Canada.

The Proposal indicates that the taxpayer claiming the ITC must make “reasonable efforts” to ensure that covered workers employed by other employers are paid prevailing wages. It is common for engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) functions to be contracted out to specialized firms. In such circumstances, the taxpayer would presumably be on the hook for making reasonable efforts to ensure that covered workers are paid prevailing wages, even though such covered workers are not employed by the taxpayer. The Proposal does not elaborate as to what “reasonable efforts” entail, and this is a grey area that will need to be confirmed.

Similarly, the Proposal indicates that the taxpayer must undertake “reasonable efforts” to ensure that apprentices spend enough labour hours where labour laws or other circumstances may otherwise hinder the ability to meet the basic apprenticeship requirements. Again, the Proposal does not elaborate as to what “reasonable efforts” entail; this should be confirmed.

10. Non-Arm’s Length Transfers

The Proposal includes a restriction on ITC-eligible costs arising from non-arm’s length transfers. In situations where an eligible property is acquired by a taxpayer (transferee) from a non-arm’s length person (transferor), the capital cost to the transferee for purposes of computing the ITC is restricted to the lower of (i) the amount paid, and (ii) the capital cost to the transferor.

Leo Berwick Insights: This directly restricts the ability to sell an asset at a premium from one related development company to another related operating company in order to boost the basis eligible for the ITC. This is a structure seen frequently in U.S. energy investments.

While this is restrictive, there may be opportunity to explore the potential benefits of retaining a non-controlling interest in both the development and operating side of the structure while ensuring that such arms of the structure are not related (e.g., by including arm’s length third-party investors). Leo Berwick will be exploring these opportunities over the coming months.

For illustrative purposes, consider a $100 premium above construction cost paid by an acquiror to a developer for a solar farm. Assume that the construction stage is just before substantial completion. The developer will recognize income and pay tax in the $20-30 range depending on their province. However, the acquiror will receive an extra $30 ITC and also receive access to additional depreciable basis of $70 (the tax benefit of which is in the $15-20 range). As such, a transfer for fair market value generates net tax benefits, and investors will want to consider the possibility of retaining an interest in both sides of the structure to potentially obtain access to these additional benefits.

How Leo Berwick Can Help

Tax structuring to maximize ITC benefits

- Availability of basis step-ups to boost the capital cost eligible for the ITC, including consideration of non-arm’s length transfers

- Optimal structuring for different investor types

Sponsor and developer tax modeling

- Compare after-tax return of developer selling asset to third party vs. retaining an interest in the operations and claiming ITC

- Consider impact to tax-exempts of holding investment in taxable structure (eligible for ITC) compared to flow-through structure (ineligible for ITC but tax-free)

Review ITC eligibility

- Consider specific capital costs and eligibility for ITC

- Perform valuation and cost analyses to support ITC eligibility

- Consider labour requirements

Tax insurance

Assist investors through the process of insuring key tax risks associated with investing in ITC-eligible projects, including:

- Cost eligibility

- FMV appraisal

- Acquisition/holding structure, including impact of transfers between entities under common ownership

- Prevailing wage and apprenticeship requirements

If you have further questions about the Proposal or the Clean Technology ITC, please contact Nick Kato, Managing Partner (nick.kato@leoberwick.com) and Zack Bhatia, CPA, Vice President (zack.bhatia@leoberwick.com).